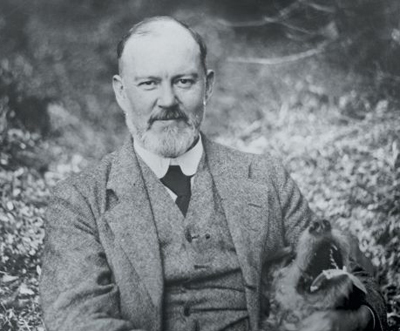

Frederick Henry Royce (27 March 1863 – 22 April 1933). Born into humble beginnings on 27 March 1863, Royce was the youngest of five children. He was a natural-born entrepreneur and his skills were largely self-taught. From his earliest successes in the infant electrical industry, which he joined in 1884 aged just 21, to his death in 1933, Royce uncompromisingly pursued his basic principle of establishing the best design, using the finest materials available, worked by the highest levels of craftsmanship. In his own words:

“Strive for perfection in everything you do. Take the best that exists and make it better. When it does not exist, design it.”

Royce’s short lived partnership with Charles Rolls established in 1904 and terminating in Rolls’ premature death in a flying accident in 1910, created the name Rolls-Royce. From the beginning Rolls-Royce stood for quality of engineering and the pursuit of excellence, but the company quickly became the definition for the best. Royce died in his 70th year at his house, ‘Elmstead’ in West Wittering, West Sussex on 22 April 1933. The house is less than 10 miles from the new Home of Rolls-Royce at Goodwood.

On March 27 1863, Frederick Henry Royce joined his three sisters and brother as a child of James and Mary Royce, of Alwalton near Peterborough. James, like his father before him was a miller. A jovial man, James lacked business skills which resulted in his bankruptcy in February 1867. At that time, the four year old Frederick had his first job, that of bird-scarer on a local farm; his pay was sixpence a week.

The family fell on hard times and were forced to split up, Mary taking her daughters to lodgings in Alwalton, and James taking the boys to London. He died in 1872, probably of Hodgkin’s disease, and Frederick’s mother arranged for him to stay in London, boarding with an elderly couple known to her from the family’s days in Alwalton.

The next year saw ten years old Frederick selling newspapers for W H Smith & Sons at Clapton and Bishopsgate railway stations close to the City of London. He probably had no more than one year at school by then, and frequently had no more of a daily diet than a couple of slices of bread soaked in milk. This period of malnutrition and long working hours contributed to his medical problems in later life.

Another year at school and a period of enforced idleness followed, during which Frederick suffered from depression, but things took a turn for the better when in 1876 he took a job for two years as a telegram delivery boy. Working from the Mayfair Post Office in central London, his beat included 35 Hill Street, where on 27th August 1877, Charles Stewart Rolls was born. It is wholly possible that the young Royce delivered congratulatory telegrams to the parents of his future partner, on the occasion of their son’s birth.

The next stage in Henry’s life was to start him on his career as an engineer. He was sponsored by his great-aunt Catherine, who paid the £20 per annum fee for him to become an apprentice at the Great Northern Railway depot in Peterborough. During this time, Royce lodged with George Yarrow and his family; George and his son Havelock also worked at the GNR depot. George had a garden shed which housed a lathe, and in the evenings he tutored the two boys in its use and that of basic tools. Three beautifully made brass model wheelbarrows survive, that Royce made in the Yarrow garden shed. Royce also studied maths and English along with the relatively new subject of electricity. Sadly, when Royce was 17, financial matters took a turn for the worse and his great-aunt could no longer pay the charge to the GNR.

Unemployed once again, Royce walked many a mile in search of work, which he finally found as a toolmaker with Greenwood & Bateley of Leeds. He stayed there during 1880-81 and then set off for London, this time with prospects of a good position with the Electric Light & Power Generator Co. The concern was soon renamed The Maxim Weston Co, as they had acquired electrical patents from Hiram Maxim, the inventor of the Maxim machine gun.

The 19 year old Royce took to electrical engineering like a duck to water, and by 1882 was appointed First or Chief Electrician of a Maxim Weston subsidiary in Liverpool, the purpose of which was to supply electric lighting to the corporation, The Prince of Wales theatre and to private homes. The venture did not last long and by May 1884 the now insolvent company was taken over by its parent. Royce, supported by some of his co-workers decided to set up on his own.

During his time in Liverpool, Royce had formed a friendship with an equally ambitious young engineer named Ernest Claremont. They decided to set up a company manufacturing small electrical components for electrical lighting systems. Using their savings, £20 from Royce and £50 from Claremont, they set up Royce & Partners Electrical & Mechanical Engineers, at 1a Cooke Street, Manchester. The partners lived in a room over the works, eating sandwiches and the odd treat warmed over an oil stove.

The first commercially successful product was an electric doorbell kit, sold for 1/6d, which funded more ambitious products. Royce was obsessed with his work and would often stay at his bench overnight. Soon, they were making dynamos, and Royce devised a sparkless commutator which opened up the use of electrical power generation in coal mines and other industries where the risk of fire and explosion was high.

By 1893, Royce and Claremont decided that they were sufficiently established to take wives, this they did by marrying the Punt Sisters, Royce walking down the isle with Minnie on the 16th March. Happily the Punt sisters were able to introduce capital of £1,500.00 into the business by way of dowries. A year later the company name changed to F H Royce and company Ltd, Frederick becoming Managing Director and Claremont Chairman. By 1895 many components were being made, but production of the most renowned of all, the Royce Electrical Crane, was about to start. A success story all its own.

In 1898 Royce, Minnie and his adopted niece moved into the newly built Brae Cottage in Knutsford. By 1902 Royce was taking an interest in motor cars, and following a visit to South Africa to recover from a collapse, Royce bought a second-hand two cylinder Decauville. It failed to start upon collection, but Royce cured the problem the next day. After running the little car for a time he worked out the many improvements that could be made, and decided rather than to modify the French car, he would build his own.

By 1907 they were producing the ‘best car in the world’ – the Silver Ghost, which would be manufactured at a new factory in Derby.

Meanwhile, Royce had met Charles Rolls, and they had formed a new company to manufacture motor cars, Rolls-Royce Limited; the demands of two World Wars necessitated the building of aero-engines as well, of course to Royce’s designs.

Sir Henry Royce, knighted in 1930, finally succumbing to digestive tract problems bought on by the early years of poor nutrition and a lifetime of overwork. He died on 22nd April 1933, having spent much of the last years of his life working from Sussex and Le Canadel in the South of France, a semi-invalid. Such was his never-failing enthusiasm and dedication to engineering, his last drawing was made from his death-bed, a few hours before he died. The drawing has a notation upon it explaining the handwriting other than Royce’s as being that of his nurse, he being too weak to write.

Although he died before the drawing reached Derby, his legacy to engineering the world over and to Rolls-Royce in particular has survived. It remains in safe hands.

Before the invention of the motor car, Royce was a highly successful electrical engineer. Here the author describes Royce’s early life and career.

THE YOUNG ROYCE

Frederick Henry Royce was the youngest child of five siblings. He was born at Alwalton Mill near Peterborough on 27 March 1863. His father, James, was a miller and he and his wife, Mary, were renting the mill from the Dean and Chapter of Peterborough. James suffered from ill-health that affected his work and he was getting into financial difficulties at the time of Royce’s birth. James mortgaged the lease he held on Alwalton Mill to the London Flour Company which then employed him. In 1867 James moved to London, still working for the Company, leaving his wife and debts behind. Sadly, James died in abject poverty in a poor house in 1872. He was just forty one years of age; the young Royce was nine.

Royce’s early years of poverty had a profound effect on the rest of his life. Following the death of his father, Royce moved to London with his mother where she struggled to make ends meet with very limited financial resources. To enhance the family income, the young Royce found work selling newspapers for W H Smith, firstly at Clapham Junction and later at Bishopsgate Station. A little later he was employed by the Post Office delivering telegrams in Mayfair. He was paid one half penny for each delivery he made.

AN INTEREST IN MECHANICS

As a boy, Royce was already taking an interest in mechanics. At the age of fourteen, he persuaded an aunt on his mother’s side of the family to pay £20 per year so that he could become an apprentice at the Great Northern Railway locomotive works in Peterborough. Royce was determined to make up for the lack of formal education in his early years so in his spare time he went to evening classes in English and mathematics.

Royce’s apprenticeship with the Great Northern Railway provided him with invaluable skills in mechanics. However, after three years his aunt was unable to continue her financial support of Royce so, at the age of seventeen, he had to leave his apprenticeship and look quickly for gainful employment elsewhere. He soon found work with a firm of toolmakers, Greenwood and Batley, in Leeds. They paid him the grand sum of one penny per hour! Royce only stayed with the firm for a short while.

AN INTEREST IN ELECTRICITY

By his late teens, Royce began taking an interest in electricity and its applications. His interest led him to answer an advertisement placed by the Electric Light and Power Company in London. Royce obtained a job with the Company and worked long hours in the factory. He became totally absorbed in his work, shunning recreation and neglecting his diet – a lifestyle pattern that was to stay with Royce for the remainder of his life.

In addition to his long working hours in the factory, Royce continued to strive to improve his education. He attended lectures and college classes on electrical engineering organised by the City and Guilds Institute and he impressed his tutors. Royce also made impressive progress in the Company and, at the tender age of just twenty, was promoted to be the Chief Electrical Engineer of a subsidiary firm, Lancashire Maxim and Weston Electric Company. The Company specialised in theatre and street lighting in Liverpool. Royce had the technical responsibility for a large municipal project in early 1884 – the complete installation of an arc and incandescent lighting system for several streets in the heart of the City. The project was a success.

Royce was beginning to grow in confidence as he was gaining more experience and accumulating knowledge in electrical engineering. However, his progress was cruelly halted when the Lancashire Maxim and Weston Electric Company failed and the firm was liquidated. Once again, Royce became one of the many unemployed.

F H ROYCE & COMPANY

By the age of twenty one years, Royce had managed to save £20 from his several years of paid employment. He decided to use his capital and knowledge to set up a small electrical and mechanical engineering company, F H Royce & Co, in Manchester in 1884. Shortly after the foundation of the company, Royce met Ernest Claremont who also had electrical experience. Claremont purchased a partnership in the Company for £50. Initially the works were located at Blake Street, Hulme, but the need for expansion caused the company to occupy a number of premises in the surrounding area. From December 1888, F H Royce & Co was operating from workshops in Cooke Street, Manchester. The association between Royce and Claremont was to last many years. Claremont later became Chairman of Rolls-Royce Ltd; the two men also became brothers-in-law.

F H Royce & Co began by making simple electrical devices such as bell sets, fuses, switches and bulb holders. Profits were used to experiment with more complex electrical devices and pursue more ambitious manufacturing projects. Soon the company was producing dynamos and electric motors and later winches and cranes. Royce’s attention to detail and engineering excellence ensured that every product he made was a considerable improvement on those of his competitors. The Royce dynamos were widely used in cotton mills, factories and ships and the company gained considerable financial success from their manufacture. Later, Royce cranes made at the Trafford Park factory were in great demand both for local use and for export. No less than nine cranes were sold for use on the Manchester Ship Canal. The Company undertook complete electrical installations of large private houses and factories.

INVENTION AND ILL-HEALTH

Royce appreciated the importance of sparkless commutation and his electric motors were used widely in the mining industry where their design improved safety by reducing the chances of a spark igniting gas. Before the days of carbon brushes, Royce understood the superiority of the drum-wound armature for continuous current dynamos. He discovered and demonstrated the cause of broken wires in dynamos caused by the deflection of the shafts by weight and magnetism. Royce saw the value in having a three-wire system of conductor, both in terms of efficiency and in economy in the distribution of electricity.

However, Royce’s prodigious inventions and innovative output, combined with the rapid expansion of the company, paid its toll on him. Royce was totally engrossed in his work. He rarely took rest breaks during the long working days. He often forgot to eat meals and he slept very little. Whilst Claremont dealt with the sales and business aspects of the company, Royce was very much the ‘workaholic’ technician; his health deteriorated.

FINANCIAL SUCCESS

In June 1894, Royce and Claremont converted their business into a limited company called Royce Ltd. The money generated was used to extend the product range and build larger dynamos and electric cranes. Orders poured in and the new firm increased its reputation for quality and reliability. In October 1897, the orders in hand amounted to £6,000. Twelve months later orders amounted to £20,000. By 1899, the company’s share capital was £30,000.

The financial success of the company during the 1880s and 1890s provided both Royce and Claremont sufficient funds to purchase houses and get married. The two partners married sisters – the daughters of Alfred Punt, a London printer – in 1893. Royce married Minnie Grace Punt. The Royces built a grand house in Leigh Road, Knutsford which, of course had its own electrical power and lighting installation. The house was designed by Alfred Waterhouse, a leading architect who was responsible for several notable buildings including the Natural History Museum in London and Manchester Town Hall. A plague, dated 1898, was placed on one of the the gable ends of the house with the reversed initials ‘FH’ for Frederick Henry and ‘MG’ for Minnie Grace surmounted by a more flambouyant ‘R’ – the symbol by which Royce was known.

Despite the Royces’ house being large and grand they called it Brae Cottage – an understatement so characteristic of Royce who always played down his achievements and success. Minnie ran the household and looked after Royce – he was still a ‘workaholic’ and needed prompting to eat and rest. At Brae Cottage, Royce added gardening to his many activities. He would often work in the garden under electric light because he was invariably at his works during the daylight hours.

ECONOMIC SLUMP

F H Royce & Co, followed by Royce Ltd, enjoyed rapid expansion and financial success for fifteen years. However, towards the end of the century, the business suffered a severe downturn. The second Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 caused a slump in trade and there was less demand for Royce’s products. The adverse economic conditions were exacerbated by the large influx to Britain of cheap mass-produced electrical components, motors and cranes from abroad – primarily from Germany and the USA. There were serious falls in the order books for Royce Ltd.

Royce faced a new dilemma in his life. Should he cheapen his products, accept lower standards of production and quality to match his competitiors? No. Such a course of action would have been diametrically opposed to Royce’s ethos – he was not prepared to accept compromise. Royce began to look for other technical projects to which he could apply his electrical and mechanical skills in order to fill the gaps that were appearing in his factory’s output. Around this time, Royce acquired his first motor vehicle, a De Dion quadricycle, which ignited his interest in the possibilities for the future of the motor car.

A NEW CHALLENGE

Royce’s ill-health continued and in 1902 he collapsed as a result of exhaustion from overwork. He slept little and had to be constantly reminded to eat and drink. His overseeing of the building of the company’s Trafford Park works added to his workload. He was concerned about the fierce competition to his business from the import of cheap foreign goods. Royce did not want a break from the business but his wife Minnie persuaded him to accompany her on a holiday to South Africa to visit her relatives. The couple were away for ten weeks. When they returned to Britain, Royce was mentally and physically refreshed. He was ready for a new challenge.

Despite suffering poverty, malnutrition and a lack of education in his early years, followed by poor health and business set-backs in his 20s and 30s, Royce fought his way to become an accomplished and successful electrical engineer. In this field he was at the forefront of discovery, invention and innovation. Royce’s unremitting quest for excellence would eventually bring him lasting fame as one of the outstanding engineers of his time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.