Charles Stewart Rolls (27 August 1877 – 12 July 1910). On 4 May 1904, the Honourable Charles Stewart Rolls travelled from London to the Midland Hotel in Manchester, England. Following the advice of fellow Automobile Club Member Henry Edmunds, Rolls had arranged to meet an engineer named Henry Royce. He was a man whose British-built motor cars were said to embody qualities of refinement and silence, the very qualities Rolls so eagerly sought in the cars sold through his London-based business, C.S Rolls and Co.

The meeting took place at a time when full public support for the motor car had yet to be won. And when the first heavier than air machines had taken to the skies, courtesy of the Wright Brothers in December 1903. It ended with Rolls returning to London in a borrowed Royce car, waking his business partner Claude Johnson at midnight and proclaiming to have “found the greatest motor engineer in the world”.

Few would have guessed this event would begin a partnership that today stands as a symbol for something very special in the respective fields of motoring and of aviation. For the grilles of the finest motor cars in the world still wear the interlinked double-R badge of Rolls and Royce, as do the engines of thousands of inter-continental jet aircraft.

The story of the engineering genius behind Rolls-Royce is well documented. Henry Royce was a workaholic, perfectionist and man for whom any form of compromise was unacceptable. His famous cri de coeur, strive for perfection in everything you do. Yet, in some historic records, Rolls’ contribution is less well defined, possibly because he died so young. Sometimes characterised as a playboy or aristocrat, his influence can be overlooked in the shadow of his partner’s imposing reputation.

But while it is certainly true that Rolls hailed from a privileged background – he was born on 27 August 1877, the son of Lord and Lady Llangattock of Monmouthshire – his story is at least as rich, and arguably far more colourful, than that of his elder partner.

For the achievements of Charles Stewart Rolls in just 32 years tower over those of most who live three times as long.

Racing driver, accomplished balloonist and only the second person in Britain to hold a pilot’s licence, Rolls was in equal measure brilliant and fearless. He lodged patents for gas engine designs and was rumoured to have developed his own prototype aircraft in the sheds at Brooklands, England. Driven by a passion for motoring at the turn of the century, he saw limitless potential in powered flight as its first decade progressed.

As a young man Rolls studied mechanics and electronics and, like Royce, was fascinated by advances in engineering. He wired the servants quarters at the family home and was never happier than when covered in oil. His penchant for tinkering with imported European cars even earned him the nickname Dirty Rolls among his peers.

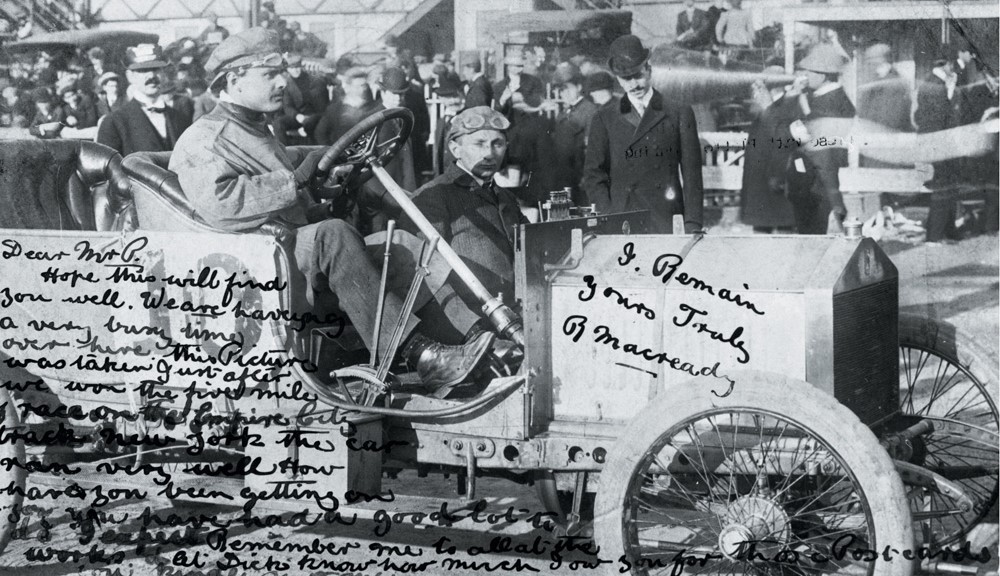

Even before the famous meeting in 1904, the name Charles Stewart Rolls would have been known to Henry Royce thanks to his exploits at the wheel and reputation as a skilled motor racer. He held the unofficial land speed record in 1903 piloting his 80hp Mors to nearly 83 mph along the course in the Duke of Portland’s Clipstone Park.

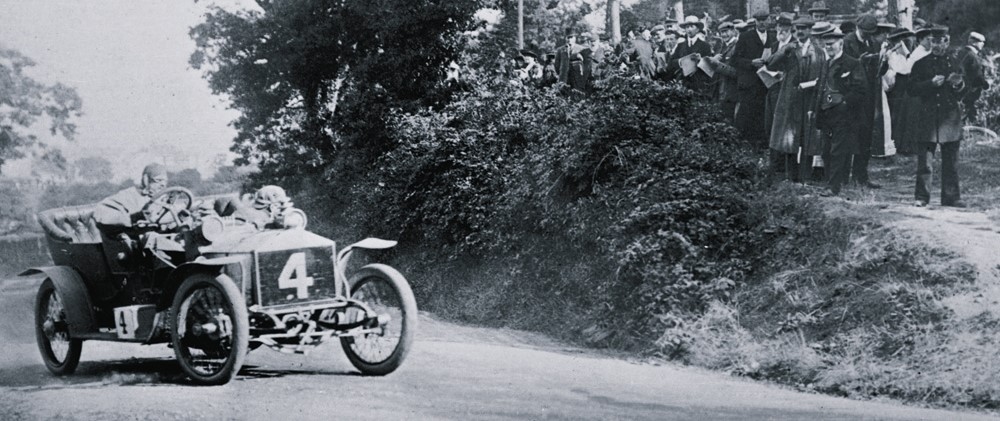

In his first race in France in 1899 – the Paris to Boulogne – Rolls had finished fourth in the tourist class, driving an 8hp Panhard and Levassor. In 1903 he competed in the fateful Paris to Madrid town-to-town, an event in which thirty-four drivers and spectators were to perish.

Following the formation of Rolls-Royce, Rolls turned his attention to the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy. After frustration in 1905, Rolls returned in 1906 winning in a Rolls-Royce Light Twenty. Upon receiving the news, staff at the Rolls-Royce plant in Derby hoisted Henry Royce aloft in triumph!

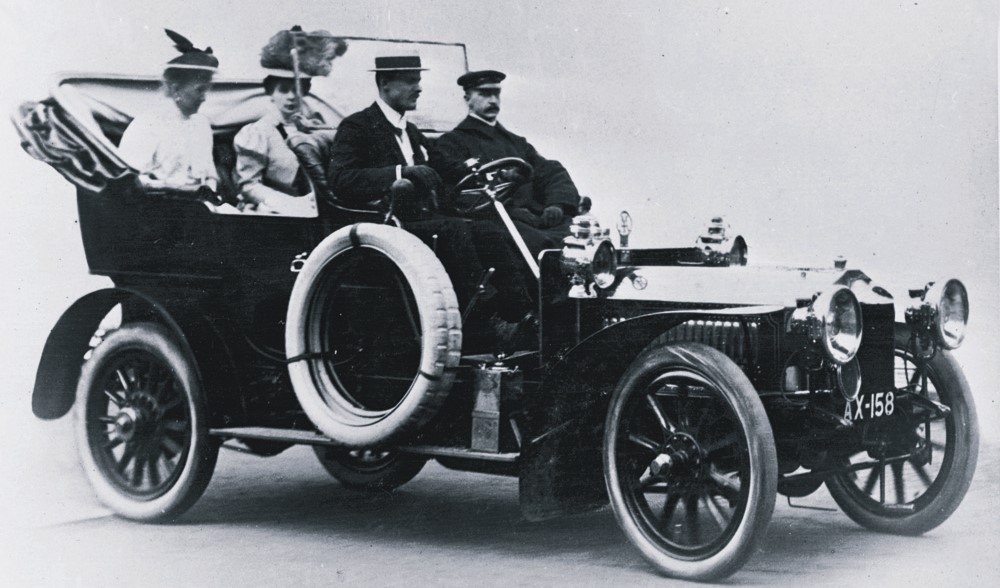

As well as a fearless racer, Rolls was a shrewd businessman who recognised the power of marketing and public relations. In his role of Technical Director, Rolls-Royce Ltd, he exploited considerable connections in the world of politics, media and in royal circles. Working alongside managing director Claude Johnson, he also knew how to work a strong story.

He supported Johnson in realising the potential of the 1906 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost, a car of exquisite beauty, quality and refinement, its metal parts coated in real silver and aluminium. It completed a 15,000 mile endurance trial emerging virtually unscathed by the experience, an incredible feat for its day. Rolls famously enjoyed demonstrating the Silver Ghost’s refinement to crowds, carefully balancing a brimmed glass of water on the running engine and watching the stunned reaction as it failed to spill a drop.

Having helped develop cars that ran endlessly without fault or breakdown, Rolls’ attention was then to turn to challenges in the air. He was one of the founding fathers of the Aero Club and made hundreds of recorded ascents in balloons. On his first flight in a powered airship, the Ville de Paris in 1907, he described the experience as, “something worth living for; it was the conquest of the air”.

By this time, Rolls was known to the Wright Brothers having met them in New York. He subsequently described himself as a frequent trespasser at the Camp d’Auvours near Le Mans in France where the Americans had taken to demonstrating their now famous flying machine.

One morning, Mr Wright turned and quietly offered Charles Rolls the opportunity which he had been patiently seeking: “Mr Rolls, I guess I’ll take you up this morning,” he said.

The effect of this first flight in 1908 was profound. Returning to earth Rolls described his experience thus:

“The power of flight is as a fresh gift from the Creator, the greatest treasure yet given to man.”

Thereafter, Rolls commissioned the Short Brothers of Battersea to build him first a glider, then a powered aircraft based on the Wright Brothers’ plans and parts.

He taught himself to fly, crashing several times while learning. He flew displays and exhibitions, then gained a world record that would win him a place in aviation history, as well as the adulation of an enthusiastic British public.

Louis Bleriot had become the first to cross the English Channel in a powered aircraft in 1909, but Rolls took this accomplishment one step further. On 2 June 1910 in a journey of 90 minutes, covering 50 miles he flew to France and back non-stop. King George sent a personal message of congratulations and one newspaper hailed Rolls as ‘the greatest hero of the day’.

By then, Rolls had resigned his position as Technical Director of Rolls-Royce and became devoted exclusively to flying, quipping that he preferred it to driving because “there are no policemen in the air.”

Sadly, shortly after this the story ended in tragedy. At an air show in Bournemouth, while Rolls pushed his Wright Flyer to the limit, disaster struck. In high winds and during a demonstration of landing skills, spectators heard a cracking noise, then watched as tail parts began to splinter and fall from his aircraft.

Plunging 70 feet, the Wright Flyer threw the 32 year old clear. He died shortly thereafter – the first British aviation casualty.

While Rolls’ life may have ended suddenly and tragically, his legacy lives on today. Before meeting Royce he professed a desire to have a motor car connected with his name in the same way that Steinway or Broadwood are connected to pianos. And thanks to the on-going tradition of building the finest, hand-built models in Goodwood, England this aspiration continues to be true.

Rolls was truly a great pioneer, “the stuff of which the best Englishmen are made,” as one friend put it shortly after his death. Driven by passion, vision and courage, his contribution to the success of the Rolls-Royce brand – on wheels and in the air – cannot and should not be understated.

You must be logged in to post a comment.