THE 1913 ALPINE TRIAL

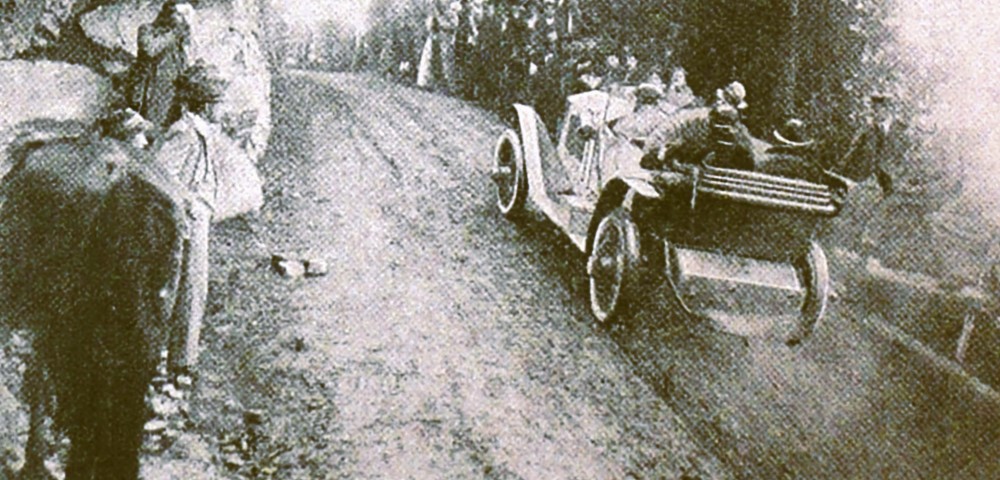

“The sight of a group of cars running up a mountain road at high speed with a superb easy gait, to which little variation in the road surface gave the semblance of a greyhound in its stride, was inspiring…” The Autocar, June 1913.

The years leading up to the 1913 Alpine Trials saw Rolls-Royce win an enviable reputation for quality and reliability. The new 40/50 hp, or Silver Ghost as it came to be known, had performed faultlessly in the landmark 1907 Scottish Reliability Trials. This success was followed with the seamless completion of the famous 1911 London to Edinburgh Top Gear Trial and Brooklands 100mph Run.

These endeavors won it the accolade, the ‘Best British Car’. However, following the events of the summer of 1913 the Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost would be known simply as ‘The Best Car in the World’.

The car’s launch heralded a period of great success for the marque. Its hallmark blend of performance, quality, smoothness and quietness endeared it to discerningly wealthy individuals the world over. Its marriage of luxury and reliability held allure for those seeking to negotiate the challenging road conditions in burgeoning markets like India and North America. In style and unabashed comfort.

However, Claude Johnson, Managing Director of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars and commercial foil to the great engineer Sir Henry Royce, sought further success in the hyper-competitive European market. A depot had been established in Paris in 1911 with further representation on the continent following in Vienna to serve the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Russia. The 1913 Alpine Trial gave him the opportunity he needed.

The Rolls-Royce Works Team

Johnson knew that success in such a high-profile European trial was imperative – and a plan of ‘characteristic thoroughness’ was hatched. He oversaw the selection and preparation of the Rolls-Royce cars and Works Team personally.

Eric Platford one of the firm’s most trusted and longest-serving employees was selected as Team Manager – his prior experience as the Honorable Charles Stewart Rolls’ riding mechanic during his victorious 1906 Tourist Trophy campaign, equipping him perfectly for the challenges ahead. Platford’s car would be driven by Curt Friese, the Rolls-Royce representative in Austria, his success vital to the planned sales push on the continent.

EW Hives, a senior member of the Experimental Department at Derby, and first man to drive the Silver Ghost at 101mph would pilot the second car. Arguably the team’s most proficient driver, he was accompanied by gifted mechanic George Hancock. The Works Team line up was completed by Jock Sinclair, a man well accustomed to the demands of Alpine motoring.

James Radley

At the time, privateer entrants also sought to pit their own Rolls-Royces against other marque’s in trials across the globe. James Radley was one of the most prolific participants.

Radley and The Honorable Charles Stewart Rolls were kindred spirits. Their lust for adventure saw their paths cross in the burgeoning aviation scene of the day. And Radley was present at the Bournemouth Air show where Rolls tragically lost his life in 1911.

Johnson decided that Radley should use his private car to set the pace for the Rolls-Royce Works Team – under the strict caveat that his personal vehicle must ‘duplicate in every way the other Alpine cars’.

This insistence stemmed from Radley’s ill-fated exploits in the Alps the previous year. With little knowledge of the severity of the terrain, he entered his 1912 London to Edinburgh specification Silver Ghost.

Rolls-Royce, who had no plans to enter a team on that occasion, was also unaware of the challenges the rally posed. The company therefore did not have to opportunity to ensure the car was correctly geared for such inclines.

The issue was compounded by Radley’s insistence on specifying the car for speed to the detriment of its hill-climbing abilities. Towards the end of the first day, on ascending the steepest part of the day’s route he came to a gentle halt, retiring himself from the rally shortly afterwards.

[Radley’s car, currently owned by Rolls-Royce collector, Mr John Kennedy will stand side-by-side with the 2013 Rolls-Royce Alpine Trial Centenary Collection Ghost at AutoChina, Shanghai in April 2013. It will also participate in the reenactment of the 1913 Trial that will take place in June this year.]

1913 Rally Preparations

Understandably, meticulous attention to every detail was considered in preparing the cars for the following year’s event. The Alps at that time of year would present an extraordinary array of challenges. Extreme temperatures, altitude and a rugged landscape peppered with water-filled gullies, pitted roads and numerous other hazards, all had to be addressed.

Most fundamental was the development of a new four-speed gearbox with low-gear designed to ensure the engine’s abundant power could be exploited on exceptional gradients. The chassis and suspension were also strengthened to mitigate against the pitfalls of traversing unmetaled roads at pace. A larger primary tank, and newly developed reserve fuel tank were developed to allow non-stop daily running.

A new starting system was also engineered to adhere to Rally regulations. These stated all bonnets must be sealed and engines must be started within one minute – no mean feat in freezing morning conditions. The solution Rolls-Royce developed worked so well, it was fitted to all production Silver Ghosts until the end of the model’s life in 1925.

Such was the importance to Johnson of a successful outcome; he put to work Derby’s finest designers, engineers and mechanics. A ‘bumping machine’ was swiftly designed and built, subjecting the proposed chassis to thousands of miles of roadwork in just a few days.

Once again, preparations for the Rally would inform normal production. The specially developed gearbox, for example, proved so perfect it would remain in use for 15 years – an extraordinary achievement considering time constraints.

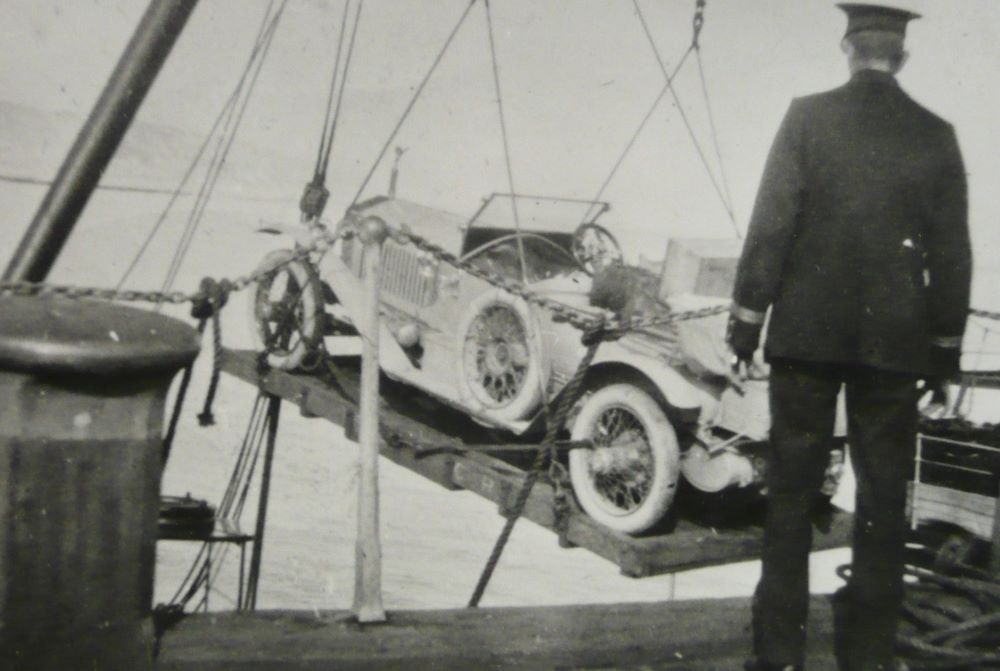

Arrival in Paris

Johnson had succeeded in producing the fastest, most durable car Rolls-Royce had developed – piloted by the most skillful drivers and mechanics in the automotive world. However, this would be for nothing without proper preparation.

Between arriving in Paris in early May 1913 and the first rally inspection on 21 June 1913, the team embarked on an exhaustive familiarisation trip. Though conditions were appalling, with unseasonably high levels of settled snow, the specially adapted Silver Ghosts were more than a match. All cars arrived in Vienna on time and without fault for their pre-rally inspections.

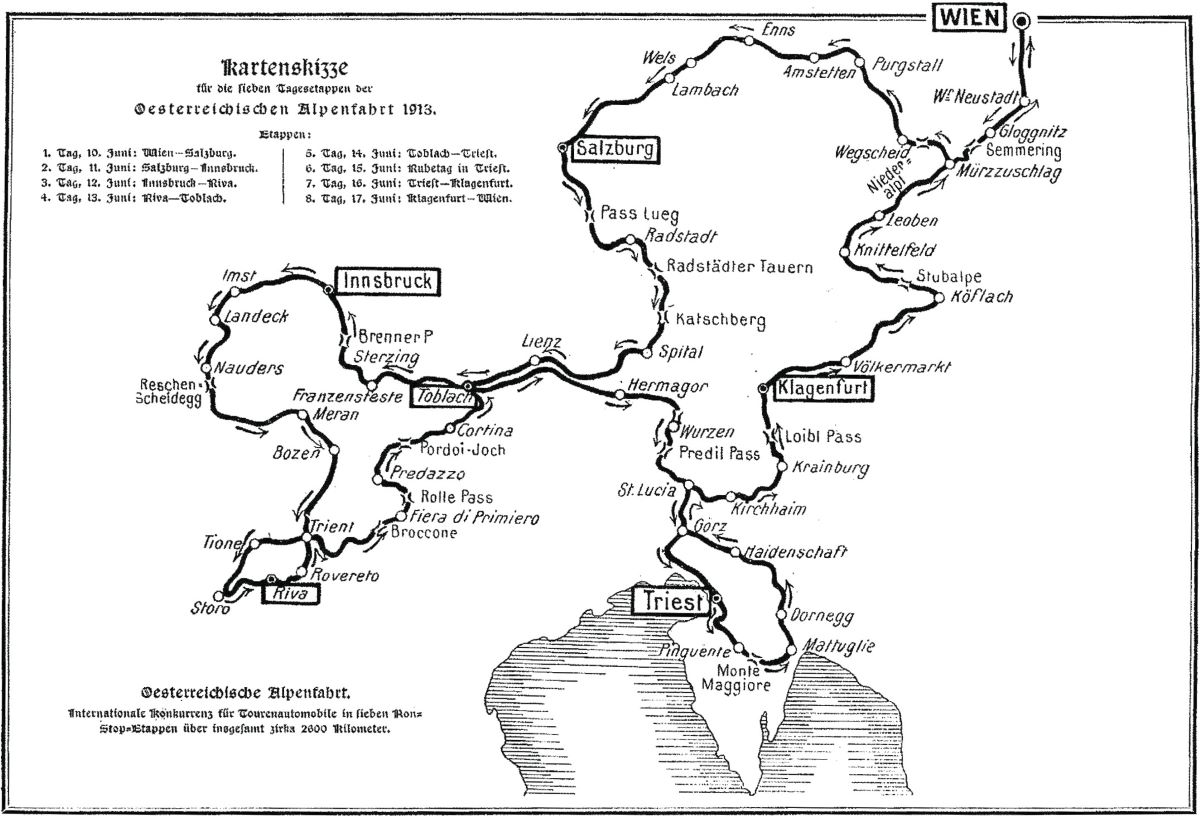

Day 1 (260 miles, 4,000 ft – highest point)

Sunday 22 June 1913

On assembly at the Vienna starting point, the Rolls-Royce Works Team drew admiration from observers, enthralled by their quietness and elegance. The cars were started in order of expected pace. As the most powerful vehicles there, the Rolls-Royce Works Team set off first.

An easy first morning was punctuated with a climb of the beautiful Semmering Pass. As planned Radley set the pace, leading the event from start to finish. The Rolls-Royce cars following closely behind at a more stately speed in their pursuit of the Team Prize.

Having set-off at 5am, Radley had completed the course by lunchtime – covering 260 miles in little over eight hours. The Works Team arrived 45 minutes later, with the Minervas the only cars near to matching their pace.

In contrast to the seamless performance of the Rolls-Royce team, a number of other marques struggled even on this relatively stately section of the rally. An English Daimler was the first permanent casualty, retiring with mechanical problems.

Day 2 (262 miles, 5,700 ft – highest point)

The morning of the Rally’s second day saw Rolls-Royce incur its first penalty. Shortly after starting his car in the permitted one minute, Hives accidentally stalled.

Once they were going, the challenge did not abate. The route was wet, muddy and slippery as they attempted to negotiate the Tauren, Katschberg and Brenner passes. Climbing 2,900 ft in just 12 miles over the oldest road in the Alps, the Tauren pass proved almost impassable to many. The Rolls-Royce team however was more than equal to its characteristic, steep 22% gradient.

It would prepare them well for what was to come. The ‘AA guide to the Alps’ said of the Katschberg “for an overgeared or overloaded car, the pass may on accession prove insurmountable,” further describing it as “a strenuous pull all the way with the unusual feature of culminating in the steepest gradient on the whole pass (27.9%).” The poor weather conditions compounded this further making for an exceptionally treacherous road surface.

The Rolls-Royce Works Team performed impeccably, driving with ease at half-throttle. Radley averaged 25mph and never fell below 17mph even on the steepest inclines. A less eventful run over the Brenner Pass to Innsbruck concluded the day’s travails.

Blistering pace over the first two days saw the team fall foul of the rally officials. They had got ahead of the official pilot car when it faltered on the Katschburg and were sternly warned against further exuberance.

Day 3 (246 miles)

The third day was more about glamour than the grit of the road. A relatively easy 246 mile run over the Reschen Pass via Meran and Trient culminated at Riva on the beautiful shores of Lake Garda. Once again the Rolls-Royce team led from the front; in fact the Autocar’scorrespondent noted Radley’s frustration at the slow pace set by the official car.

That evening, participants were treated to a grand reception – replete with a procession of illuminated boats and fireworks, framed sublimely by the magnificent mountain backdrop.

Day 4 (192 miles, 7,400ft – highest point)

Day four presented participants with a spectacular but attritional drive across the Dolomites, culminating in an ascent of the 7,400 ft Pordoi pass – the highest point of the rally. The Goberra and Broccone passes offered keen drivers an engaging succession of magnificent sweeping hairpins.

As the route wound towards Cortina and Toblach, rain and overcast skies rather spoiled an otherwise beautiful section of the rally. This rain soon turned to heavy snow. A reminder to the ever-exuberant Rolls-Royce Works Team was served when a chasing Menerva skidded and slid into a verge. The car suspended itself in a ditch, ending the Minerva’s chances in the event. Miraculously nobody was hurt.

Day 5 (205 miles, 3,500 ft – highest point)

Freezing conditions greeted competitors on the fifth day. Despite this, the three Rolls-Royce team cars started within the allotted minute without fault. However, much to his chagrin, Radley incurred a penalty on requiring three minutes to start his car.

He recovered almost immediately propelling himself and his three compatriots to their accustomed position at the front. The route returned the cars to Austria, presenting a long drive through the South of the country via the steep and pitted Wurzen pass. Hairpins were once again the order of the day as they traversed the Perdils before a statelier run through the pretty valleys to the port city of Trieste. The Rolls-Royce cars were again unmatchable in speed and ability to excel in all conditions.

Day 6 (242 miles, 3,500 ft – highest point

A rest day that included a leisurely cruise around the bay of Trieste preceded one of the most challenging points in the rally. The steepest of all the passes, the Loibl had to be overcome before the final overnight stop at Klagenfurt. Rising 2,300 ft in just three miles, every bit of guile and experience was required of the pilots to negotiate the severe hairpin bends that characterised the ascent.

The fastest a car had ever climbed the hill was in six and a half minutes. Radley reached the summit in five and much to the amusement of onlookers, refreshed himself with a drink as he rounded the final hairpin.

The Rolls-Royce team, of course, arrived first in Klagenfurt.

Final day disaster (260 miles, 5,000ft highest point)

The final run from Klagenfurt to Vienna presented new challenges. The notorious Stubalpe Pass was home to no less that 125 gullies designed to allow water to drain across the road. They could only be negotiated at walking pace. Conditions proved so challenging the official pilot car stopped before the main ascent, allowing another, more adept pilot to take over.

The Rolls-Royce team negotiated the challenge faultlessly before embarking on the relatively easy and fast final leg to Vienna. Radley hit 70mph on three occasions and only had to ease off as he risked falling foul of the officials by once again catching the pilot car.

Leading as they approached Vienna on the final leg of the rally, the Rolls-Royce Works Team could have been forgiven for taking the opportunity to enjoy something of a lap of honour. However, disaster struck in the small village of Guntramsdorf.

Sinclair, who had accrued no penalty thus far, was struck by a speeding Minerva (a car that had previously harassed two other Rolls-Royces on the rally) piloted by a non-competitor. The impact to the side of his car forced him onto a telegraph pole.

Displaying extraordinary guile and presence of mind, Sinclair managed to keep the engine running. However, the near-side wheel was broken, its tyre burst and the offside running board completely destroyed and the change speed and handbrake lever were irreparably damaged.

The wheel was repaired and Sinclair found he could still engage third gear, limping the rest of the way to Vienna in one gear.

This was the only day the Rolls-Royce Works Team failed to finish in the first four positions.

Final Standings

Only 31 of the original 46 entrants reached Vienna. After a long process of inspections, the results were announced. The Rolls-Royce driven by Friese and Platford was one of only four cars to have performed without penalty.

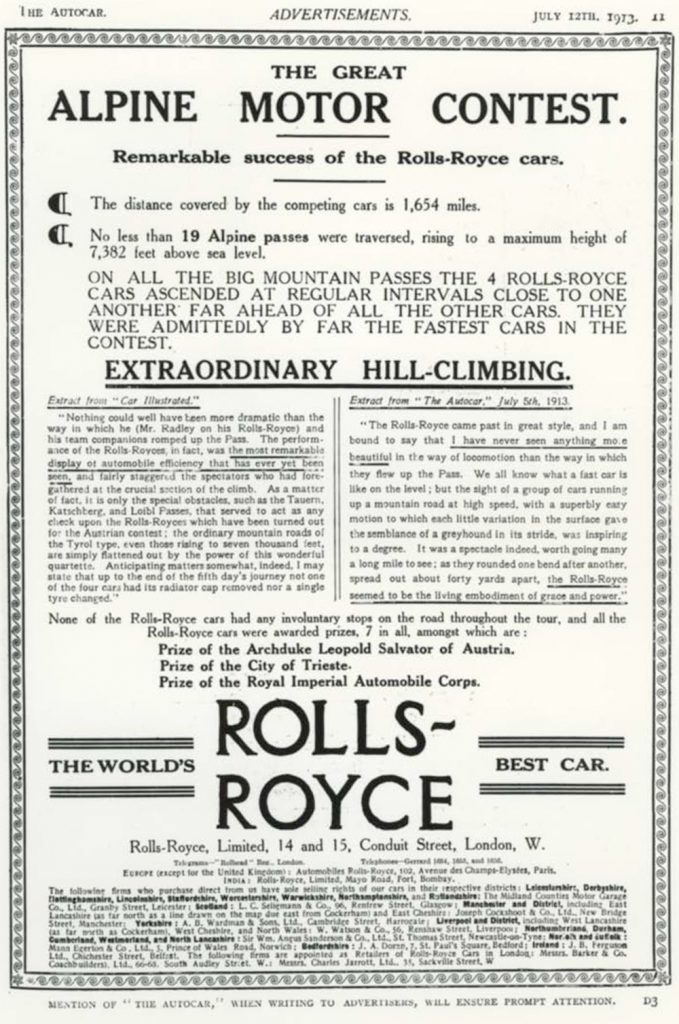

Rolls-Royce was heralded as the stars of the rally with people marvelling at their speed and strength. Frieze and Platford’s faultless performance and pace was rewarded with the most prestigious individual prizes presented by the Archduke Leopald Salvador. Radley was honoured with the City of Trieste’s Prize.

A worthwhile endeavour?

The marque’s exceptional performance drew universal praise across the automotive world. Observers marvelled that fully equipped luxury tourers – rather than adapted competition cars – were able to climb such steep inclines, effortlessly and at such speed. The fact they finished as front-runner on every day, but the unlucky last, compounded this sentiment further.

In terms of satisfying Johnson’s desire for success on the Continent, the Alpine Trials proved an emphatic success. Following the rally, sales in Europe grew to match those in the UK – an exceptional result.

The Alpine Trials continued until 1973. However, Rolls-Royce never entered a Works Team –again – the legend of the ‘Best Car in the World’ had been established.

You must be logged in to post a comment.