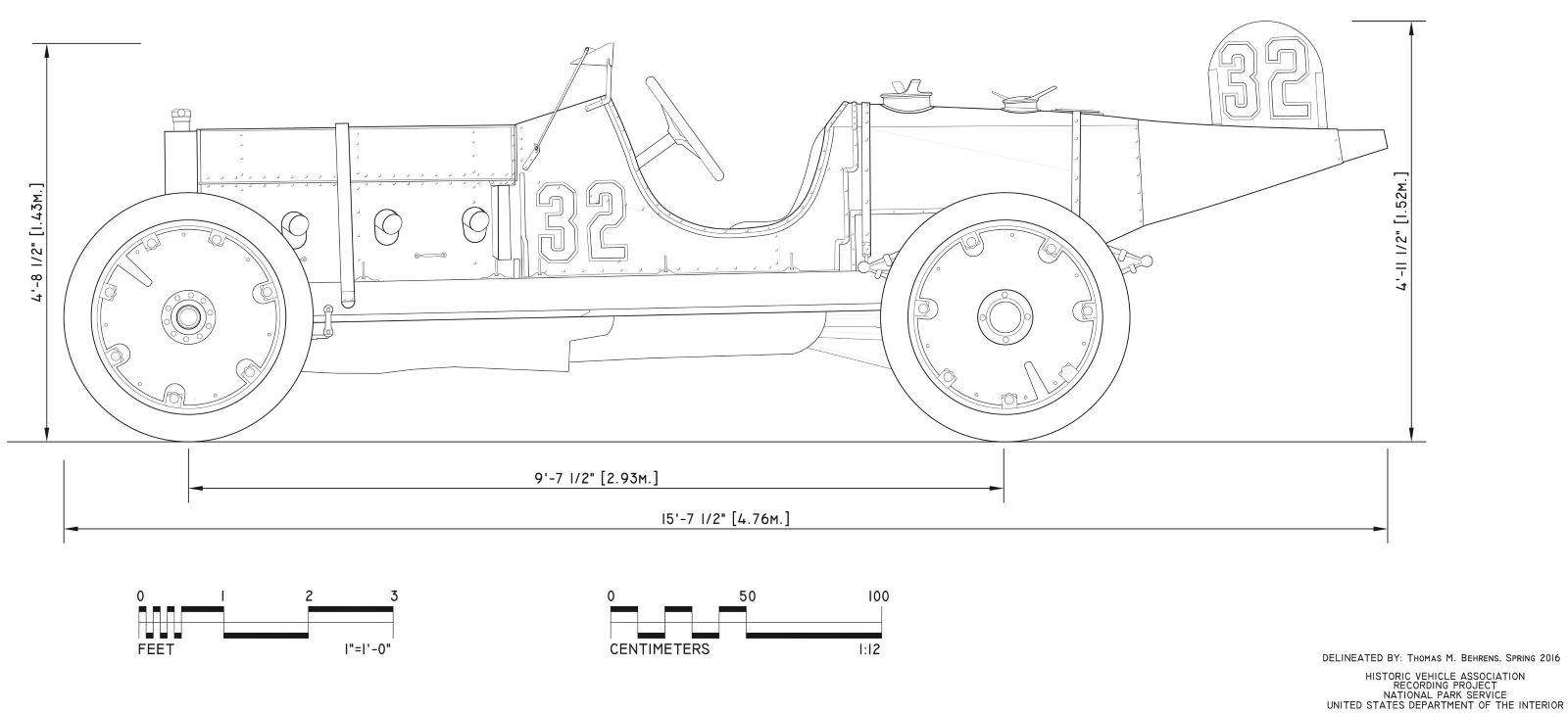

The Marmon Wasp, one of America’s most historic automobiles that was driven to victory in the first Indianapolis 500 race in 1911. The Marmon Wasp is owned by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum. In May 2016, the Marmon Wasp was honored as the eleventh vehicle on the HVA’s National Historic Vehicle Register just prior to the start of the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500. The HVA manages the National Historic Vehicle Register in partnership with the U.S. Dept. of the Interior’s Historic American Engineering Record archived in the Library of Congress. To date, the Marmon Wasp has been extensively documented, measured, 3D scanned and filmed in motion by the HVA under the same Secretary of the Interior’s Standards used to record the Statute of Liberty and Space Shuttle Discovery. Once complete, the material will permanently reside in the Library of Congress, joining the archives of other iconic vehicles such as the Shelby Cobra Daytona Coupe prototype, the first White House Limousine and the Buick Y-Job. The program is a public/private partnership funded through the HVA to preserve and share America’s automotive heritage.

The Marmon Wasp was raced at the 1911 Indianapolis 500 by Ray Harroun who along with Howard Marmon designed the car. The car was a study of innovation from nose to tail. Up front the Wasp used a four shock system to counteract the bumpy conditions of the dirt and gravel surfaces and unpredictability of the new brick surface at Indy. Harroun, the consummate engineer, determined that speeds over 80 mph were disastrous for tires so he kept his speed in check and only changed two tires during the race.

The second place car by contrast changed tires fourteen times during the race. The engine was a special design as well adding two more cylinders to the four used in the Marmon 32 Model which was already quite successful in racing. The cockpit was designed only for the driver at a time when racing was typically a two man affair with driver and riding “mechanician.” This shaved significant weight off the car with a narrower body and one less passenger aboard.

To accommodate the steering position a gear system was devised to move the steering column to the center of the cockpit. The tail was also unusual in the style of an airplane tail and stabilizer which is not surprising as Harroun was flying the steel monoplane he designed just one month before the 1911 race. Perhaps the cleverest feature was the rear view mirror he installed before the race to address the fear that his driving solo would endanger other racers because he would be without a mechanician on look out. The installation of the rear view mirror centered above the cockpit was apparently inspired by use on a carriage he saw in Chicago years before. Years later Harroun said that the mirror was unfortunately useless during the race because it shook too much.

The story of the Marmon Wasp is the story of the greatest personal accomplishment of one of America’s most gifted engineers, race drivers and entrepreneurs. Ray Harroun was born in 1879 in the small town of Spartanburg just south of Erie, Pennsylvania. By the time he was twenty-four, this dentist and chauffer turned race driver was part of a four -man driving team that set the record for the Chicago to New York trip in 1903 and 1904. In addition to the rear view mirror innovation, Harroun also invented the first automobile bumper.

His inventiveness and business acumen likely provided the funding he needed to produce his first race car, an 8-cylinder car that averaged over 116 mph on a one-mile run at the Daytona-Ormond Beach events in 1907. He then was contracted by the Nordyke & Marmon Co. of Indianapolis to develop a fast stock car for racing. Over the next several years he became a national celebrity as one of America’s winningest race drivers primarily in the Marmon Model 32.

He retired after the 1910 season — for which he was officially honored as National Champion many years later. In 1911, the new safer brick surface and chance to win the first Indianapolis 500-mile race along with the sizable purse were enough to persuade Harroun to return to the track one last time. The “Little Professor” as he was known by the press “dopesters,” drove into history on Tuesday, May 30, 1911 by winning the first Indianapolis 500.

He quit “the game” as it was called in that time, as a man on top never to race again. He went on to design successful race cars for Maxwell and his own lightweight Harroun automobiles between 1916 and 1922. These cars were priced very competitively at just under $600. About 500 Harroun cars were produced. Harroun also invented a highly successful kerosene carburetor to deal with the variability of fuels during the period and had a roll in defense manufacturing during WWI.

Throughout his life he was honored for his accomplishments but foremost as the first winner of the first Indianapolis 500 and the engineering mind behind the innovative Marmon Wasp — the first single seat, open-wheel race car. In 1916, he was honored by Motor Age magazine along with Fred Duesenberg and Louis Chevrolet as one of the ten top engineers “who have made possible present racing cars and speed records.” Ray Harroun worked as an engineer into his seventies and passed away in 1968 at the age of 89 as an American racing legend and one of the great pioneers of performance.

Facts You Will Want to Know About the First Winner, the Marmon Wasp

Luxury Performance –

Initially avoiding the trend set by Ford for low-priced, high-volume cars, Marmon focused squarely on the high-end market with an eye on speed. Early marketing included hiring Helen Keller as a spokeswoman, fielding cars in races around the country – where Ray Harroun won over forty-one races in 1910, and sending a 1916 Model 34 across country in six days breaking the previous record held by Cannon Ball Baker. Their production cars gained a reputation as reliable and fast upscale automobiles. Marmon, like its luxury competitors, couldn’t survive the Great Depression, however. Despite introducing a lower cost car in the late 1920s, the company built its last automobile – the sixteen-cylinder Series 16 – in 1933.

Factory Hot Rod –

Ray Harroun, an engineer for the Marmon Motor Car Company, designed the six-cylinder Marmon Wasp from stock Marmon engine components, adding two cylinders to the production Model 32 engine on which it was based. The Marmon, originally dubbed “Yellow Jacket” by the media and later shortened to “Wasp,” was built with a cowled cockpit and a long pointed tail to reduce air drag, and adorned with a yellow and black paint scheme. The car also featured another important innovation – the rear view mirror. Ray Harroun was the first driver to race without a riding mechanic to watch for cars from behind and it is believed that the Marmon was the first car equipped with this vital piece of equipment.

Must Drive 75 – The 1911 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes Race Grid

Out of the 46 entries, only 40 were able to achieve the 75 mph along the quarter-mile straight required in order to qualify. Cars started based on their entry date (also their car number) rather than qualifying time. Joining Harroun for the historic rolling start were racing legends such as Ralph de Palma in a Simplex, Bob Burman in a Benz and runner up Ralph Mulford in a Lozier.

One and Done –

Ray Harroun and the Marmon Wasp started in row 6 in the 28th position. He completed the 500 -mile race in 6 hours, 42 minutes and 8 seconds with an average speed of 74.49 mph. Harroun, preferring his engineering career over that of a motorsports celebrity risking life and limb never raced again. Marmon likewise retired from official competition, content with the boost in sales provided by the 1911 victory.

Birth of a Legend –

The inaugural Indy 500 made an indelible mark on international motor racing, quickly becoming one of the premier motorsports competitions in the world. Despite a few off years due to WWI and WWII, the race has been run continuously since 1911. This year marked the 100th running of what has become the largest single day motorsports spectator event in the world.

You must be logged in to post a comment.