The prototype of all modern passenger cars

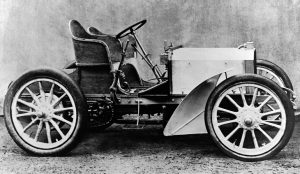

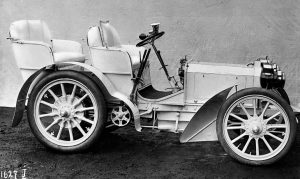

At the turn of the century, the Mercedes 35 hp, the prototype of all modern passenger cars, was the definition of a fundamentally new and ever since prevailing vehicle architecture: it marked the transition from the long-legged “motor carriage” to the motor car as we know it today. The decisive technical innovations were its long wheelbase, wide track, low centre of gravity and angled steering column. These improvements created the basis for comfortable and safe driving, something that was first turned into reality in a Mercedes.

There are also some characteristic features such as the elongated form and the honeycomb radiator, which, organically integrated into the front end, was to finally solve the hitherto omnipresent problem of how to cool the engine, quite apart from emerging as a distinguishing mark of the brand. With its light-alloy crankcase, the powerful four-cylinder engine served as a model for today’s still current lightweight design and was, furthermore, installed low in the frame. Its exhaust valves were controlled by a camshaft, this significantly improving the smoothness of operation, stability at idle and acceleration. The construction principle of “engine at the front, final drive to the rear wheels” was to establish itself in the long term as the conventional drive layout.

35 hp Mercedes

The “35 hp” was the first vehicle to sport the Mercedes brand name and went down in history as the first modern-day motor car. Many other manufacturers were to copy this innovative concept, which proved to be superior in every respect. Mercedes-Benz thus from an early date established its claim to be the leader in technology and design.

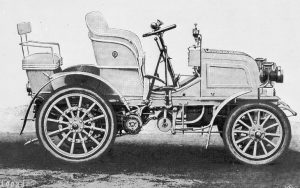

Emil Jellinek in March 1900, under the pseudonym “Mercedes”, entered two Daimler “Phoenix” racing cars with 28 hp engines in the Nice race week. To support him, Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG) sent Wilhelm Bauer, an experienced master mechanic who knew the vehicles inside out. On the 30th of the same month, Wilhelm Bauer had a fatal accident in the very first curve of the hill climb race from Nice to La Turbie.

This marked the end of the Daimler “Phoenix” cars: afterwards, DMG adopted a highly reserved attitude to motor sport. Emil Jellinek, however. As early as April 2, 1900, demanded a more competitive car from DMG, with higher performance but at the same time a lighter engine, a longer wheelbase and also a lower center of gravity. Also, the engine to be newly developed was to bear the name “Daimler-Mercedes”.

For the first time, the name “Mercedes” appeared as a brand name and no longer merely as a team or driver name. In Jellinek’s opinion, the only one capable of realizing his ideas was Wilhelm Maybach, the ingenious technical brain of DMG. To give emphasis to his detailed wishes, Jellinek also ordered 36 vehicles from DMG, with a total worth of 550,000 Marks – in today’s terms about DM 5.5 million: a sensationally large order for DMG, and more were to follow later. As matters stood, only an extensively new design came into consideration for the car demanded by Jellinek. But how could this be done in the remaining, unusually short time before October 15, the desired delivery date?

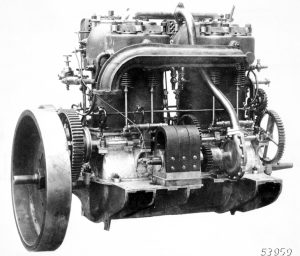

First of all, Maybach developed the new engine for the “Mercedes” car, the outline for which was already in his mind. The horizontally divided crankcase was for the first time made from aluminum. The cylinders, made in pairs from gray cast iron, featured cylinder heads which formed part of the castings, unlike the removable ones in the “Phoenix” car. With a bore/stroke ratio of 116 x 140 mm, the engine had a total displacement of 5918 cc, a good 400 cc more than in the “Phoenix” car.

For the main bearings, Maybach used magnalium, an aluminum alloy containing five percent magnesium. Like the exhaust valves, the intake valves, which until then had been designed as ‘snifting’ valves – opened by the vacuum pressure inside the engine – were now controlled by a camshaft. The non-encapsulated camshafts to the left and right of the crankcase were driven by an open toothed-gear power take-off on the flywheel side.

Via a gear set arranged in its center, the exhaust camshaft drove the low-voltage ignition magnets and a water pump for improved cooling efficiency, while a further gear set at the front end drove a small fan behind the radiator. Another new feature: each cylinder pair had its own separate carburetor. In the range between 300 and 1000 revolutions, engine speed was controlled via a lever on the steering wheel.

All these improvements ultimately resulted in much smoother operation, more stable idling and good acceleration – a new quality in engine characteristics, which at that time was hardly believed possible. In addition to this the engine weight was reduced by 90 kg to around 230 kg.

Maybach no longer installed the engine into a chassis sub frame, as was usually the case at that time. Instead, he narrowed the front frame section ahead of the pedal level, permitting the engine to be directly bolted to the side members. The latter were no longer laboriously beaded but for the first time made of pressed sheet steel by DMG. Both these measures not only reduced the weight but also provided for the lower center of gravity that Maybach was aiming at.

Another completely new design was the highly compact and automatically adjusting clutch, a coil spring made of spring steel, which with the help of a small drum was attached to the transmission shaft and fastened inside the flywheel. Further development of the car at a later stage benefited from this design. A conical cam regulated the spring tension during declutching.

The four forward gears and the reverse gear were engaged by means of a single lever in a shift gate. This feature was as new as the improved, light steering with its worm gear – a unit installed further to the rear and at a relatively steep angle. The steering axles were moved further toward the outside, closer to the wheel hubs, thereby significantly reducing the impact of road shocks on the steering.

Longer wheelbase, wider track, more effective brakes

Compared to the “Phoenix” car, the wheelbase was markedly longer (2245 millimeters) and the track wider (1400 mm) – giving the new car significantly greater stability. Apart from that, wheels of virtually the same size were now, at last, used on the two axles, albeit in the traditional wooden twelve-spoke design.

The brakes were adapted to the higher engine output, thus the “Mercedes” was fitted with 30 centimeter drum brakes on the rear wheels, operated via a manual lever and a linkage, and with an additional foot-operated brake.

One of the most sensational inventions on this first “Mercedes” – and one that has essentially remained unchanged to this day – was the honeycomb radiator.

Until then, coiled pipe radiators had customarily been used, their efficiency leaving much to be desired. They had caused an enormous water consumption or required very large and therefore heavy coolant circuits. Maybach had taken a major step toward the solution of the cooling problem as early as 1897 when he introduced a radiator consisting of a large number of small tubes which were flushed by coolant and additionally cooled by airflow. The latter permitted a marked reduction in the required coolant reservoir which, however, was still a sizeable 18 liters.

Maybach achieved a major breakthrough with the honeycomb radiator first incorporated in the “Mercedes”. He had as many as 8,070 small square tubes, each six by six millimeters in size, soldered together into a completely novel, rectangular radiator. Cooling efficiency was considerably increased and water consumption reduced by half to a mere nine liters by the square tubes’ larger passage cross-section and the smaller gaps between the tubes. A small fan behind the radiator improved cooling efficiency at slow speeds. The honeycomb radiator had been born –the automotive cooling problem had become a thing of the past.

The new car was for the first time tested on November 22, 1900, and the first “Mercedes” was delivered to Jellinek on December 22. Before long, the styling design of the first “real” car in history set the trend for the rest of the automotive industry, causing a ‘landslide’ in design. The car’s elongated silhouette, high performance, honeycomb radiator, low-slung engine hood, long wheelbase, shift gate, obliquely installed steering, equal-sized wheels on the two axles and low weight were from then on regarded standard components of the modern automobile.

The sensational successes in racing in 1901 of the Mercedes cars gave credit to Maybach’s new design. People also highly appreciated the fact that the two-seater, once it was no longer used for racing, was easily converted into an elegant four-seater by means of a rear bodywork element that could be installed in just a few minutes – the ideal car for cruising on fashionable avenues and promenades.

Gallery

You must be logged in to post a comment.