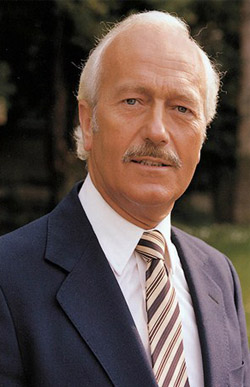

Anthony Colin Bruce Chapman (1928 – 1982) was an influential English design engineer, inventor, and builder in the automotive industry, and founder of Lotus Cars. He studied structural engineering at University College London, joined the University Air Squadron and learned to fly in the Mid 40’s.

Anthony Colin Bruce Chapman (1928 – 1982) was an influential English design engineer, inventor, and builder in the automotive industry, and founder of Lotus Cars. He studied structural engineering at University College London, joined the University Air Squadron and learned to fly in the Mid 40’s.

In 1948 Chapman started with the Mk1, a modified Austin 7, which he entered privately into local racing events. He named the car “Lotus”; he never confirmed the reason but one (of several) theories is that it was after his then girlfriend (later wife) Hazel, whom he nicknamed “Lotus blossom”. With prize money he developed the Lotus Mk2.

In 1952 he founded Lotus Cars. Chapman initially ran Lotus in his spare time, assisted by a group of enthusiasts. His knowledge of the latest aeronautical engineering techniques would prove vital towards achieving the major automotive technical advances he is remembered for. He was famous for saying “Adding power makes you faster on the straights. Subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere”, as his design philosophy focused on cars with light weight and fine handling instead of bulking up on horsepower and spring rates.

With continuing success on through the Lotus 6, he began to sell kits of these cars. Over 100 were sold through 1956. It was with the Lotus 7 in 1957 that things really took off, and indeed Caterham Cars still manufacture a version of that car today – the Caterham 7; there have been over 90 different Lotus 7 clones, replicas and derivatives offered to the public by a variety of makers.

In the 1950s, Chapman progressed through the motor racing formulae, designing and building a series of racing cars, sometimes to the point of maintaining limited production as they were so successful and highly sought after, until he arrived in Formula One. Besides his engineering work, he also piloted a Vanwall F1-car in 1956 but crashed into his teammate Mike Hawthorn during practice for the French Grand Prix at Reims, ending his career as a race driver and focusing him on the technical side. Along with John Cooper, he revolutionised the premier motor sport. Their small, lightweight mid-engined vehicles gave away much in terms of power, but superior handling meant their competing cars often beat the all-conquering front engined Ferraris and Maseratis. Eventually, with legendary driver Jim Clark at the wheel of his race cars, Team Lotus appeared as though they could win whenever they pleased. With Clark driving the legendary Lotus 25, Team Lotus won its first F1 World Championship in 1963. It was Clark, driving a Lotus 38 at the Indianapolis 500 in 1965, who drove the first ever mid-engined car to victory at the fabled “Brickyard.” Clark and Chapman had become particularly close and Clark’s death devastated Chapman, who publicly stated that he had lost his best friend.

Among a number of legendary automotive figures who have been Lotus employees over the years were Mike Costin and Keith Duckworth, founders of Cosworth. Graham Hill worked at Lotus as a mechanic as a means of earning drives.

Chapman, whose father was a successful publican, was also a businessman who introduced major advertising sponsorship into auto racing; beginning the process which transformed Formula One from a pastime of rich gentlemen to a multi-million pound high technology enterprise. It was Chapman who in 1966 persuaded the Ford Motor Company to sponsor Cosworth’s development of what would become the legendary DFV race engine.

Many of Chapman’s ideas can still be seen in Formula One and other top-level motor sport (such as IndyCars) today.

He pioneered the use of struts as a rear suspension device. Even today, struts used in the rear of a vehicle are known as Chapman struts, while virtually identical suspension struts for the front are known as MacPherson struts.

His next major innovation was the introduction of monocoque chassis construction to automobile racing, with the revolutionary 1962 Lotus 25 Formula One car. The technique resulted in a body that was both lighter and stronger, and also provided better driver protection in the event of a crash. Although a new concept in the world of motorsport, the first vehicle to feature such a chassis was the road-going 1922 Lancia Lambda. Lotus had been an early adopter of this technology with the 1958 Lotus Elite. The modified monocoque body of the car was made out of fibreglass, making it also one of the first production cars made out of composite materials.

When American Formula One driver Dan Gurney first saw the Lotus 25 at the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort, he was so struck by the advanced design that he invited Chapman to the 1962 Indianapolis 500, where Gurney made his Indy début. Following the race, Chapman prepared a proposal to Ford Motor Company for an aluminium monocoque Indianapolis car using a 4.2-litre aluminium V-8 Ford passenger car engine. Ford accepted the proposal. The Lotus 29 debuted at Indianapolis in 1963, with Jim Clark finishing second. This design concept fairly quickly replaced what had been for many decades the standard design formula in racing-cars, the tube-frame chassis. Although the material has changed from sheet aluminium to carbon fibre, this remains today the standard technique for building top-level racing cars.

nspired by Jim Hall, Chapman was among those who helped introduce aerodynamics into Formula One car design. Lotus used the concept of positive aerodynamic downforce, through the addition of wings, at a Tasman Formula race in early 1968, although Ferrari and Brabham were the first to use them in a Formula One race at the 1968 Belgian Grand Prix. Early versions, in 1968 and 1969, were mounted 3 feet (0.91 m) or so above the car, in order to operate in ‘clean air’ (air that would not otherwise be disturbed by the passage of the car). The underdesigned wings and struts failed regularly, however, compelling the FIA to require the wing mounting hardware to be attached directly to the sprung chassis. Chapman also originated the movement of radiators away from the front of the car to the sides, to decrease frontal area (lowering aerodynamic drag) and centralising weight distribution. These concepts remain features of virtually all high performance racing cars today.

Under his direction, Team Lotus won seven Formula One Constructors’ titles, six Drivers’ Championships, and the Indianapolis 500 in the United States, between 1962 and 1978. The production side of Lotus Cars has built tens of thousands of relatively affordable, cutting edge sports cars. Lotus is one of but a handful of English performance car builders still in business after the industrial decline of the 1970s.

Chapman was also an innovator in the business end of racing. He was among the first entrants in Formula One to turn their cars into rolling billboards for non-automotive products, initially with the cigarette brands Gold Leaf and, most famously, John Player Special.

Chapman, working with Tony Rudd and Peter Wright, pioneered the first Formula One use of “ground effect”, where a low pressure was created under the car by use of venturis, generating suction (downforce) which held it securely to the road whilst cornering. Early designs utilized sliding “skirts” which made contact with the ground to keep the area of low pressure isolated.

Chapman’s next planned a car that generated all of its downforce through ground effect, eliminating the need for wings and the resulting drag that reduces a car’s speed. The culmination of his efforts, the Lotus 79, dominated the 1978 championship. However, skirts were eventually banned, because the skirt could be damaged, for example, from driving over a kerb, and downforce would be lost and the car could then become unstable. The FIA made moves to eliminate ground effect in Formula One, by requiring flat bottom cars from 1983 and raising the minimum ride height of the cars from 1981. Car designers have managed to get back much of that downforce through other means, aided by extensive wind tunnel testing.

One of his last major technical innovations was a dual-chassis Formula One car, the Lotus 88 in 1981. For ground effect of that era to function most efficiently, the aerodynamic surfaces needed to be precisely located and this led to the chassis being very stiffly sprung. However, this was very punishing to the driver, resulting in driver fatigue. To get around this, Chapman introduced a car with two chassis. One chassis (where the driver would sit) was softly sprung. The other chassis (where the skirts and such were located) was stiffly sprung. Although the car passed scrutineering at a couple of races, other teams protested, and it was never allowed to race. The car was never developed further.

Chapman suffered a fatal heart attack in 1982, aged 54. Chapman was married to Hazel. He has two daughters and one son. From 1978 until his death, Chapman was involved with the American tycoon, John DeLorean, in his development of a stainless steel sports car, to be built in a factory funded by the British government. Approximately £10 million of British taxpayers money, equivalent to £40 million in 2010, went missing. Chapman died before the full deceit unravelled.

Monza, Italy. 6-8 September 1963. Jim Clark (Lotus 25 Climax) gives team boss Colin Chapman a lift, as they celebrate finishing in 1st position and clinching the drivers and constructors World Championship titles.

You must be logged in to post a comment.