The Race Car That Changed Everything

Genesis

When Henry Ford began building “Sweepstakes” in 1901, he had a specific purpose in mind: publicity and recognition.

In late 1900, Henry Ford’s fortunes were at a low ebb. His first venture in auto manufacturing, the Detroit Automobile Company, was going out of business after producing 19 or 20 vehicles in a year of operation. The cars had not sold well and Ford wanted to develop a better one, but his stockholders decided to dissolve the company.

The car Ford wanted to build would be mass-produced, uncomplicated, reliable, and sold at a price most people could afford. That was a revolutionary idea in 1901, when the automobile was still a novelty, and much too expensive for all but the very wealthy.

In fact, at that time Henry Ford was thought of in Detroit as being a bit of an eccentric. He was not well known, especially beyond Detroit. He had been a mechanical engineer at the Edison Illuminating Company when he produced his first working automobile, the Quadricycle of 1896. That car brought him some local recognition, but nothing like the sensations being created in the press by famous drivers and builders like Alexander Winton, Frank Duryea, Ransom E. Olds, and particularly such European racers as Henri Fournier and Fernand Charron.

Many years later when recalling that time, Ford said, “I never thought anything of racing, but the public refused to think about the automobile as anything but a fast toy. Therefore, we had to race.”

Racing proved the worth of a builder’s engineering talent by demonstrating the speed and reliability of the product. There was a lot to prove, because the infant auto industry of 1901 was bursting at the seams with ideas, experiments and innovations. It was in a state of entrepreneurial ferment: Total U.S. auto production was about 4,000 units, from more than 50 companies, and the short lifespan of the Detroit Automobile Company was not unusual. No one knew what course the industry would take. At the turn of the last century New England was the auto manufacturing hub, not Detroit, and the predominant sources of power for automobiles were steam and electricity, not gasoline.

Sweepstakes – A Gamble

Henry Ford was confident that somebody would succeed in producing the mass-market car he envisioned, and above all else he wanted to be the one to do it. But that would require significant financial investment. He needed to prove to potential backers that he had good, sound ideas, and that his automobiles could be a commercial success. Racing Sweepstakes would provide a high-profile way to promote his name and reputation.

Still, Sweepstakes was a gamble. Fame, as well as significant prize money, could be won, but only if the car proved to be a winner. And Ford was facing tough odds. There were plenty of successful builders and racers to provide fierce and experienced competition.

Construction of Sweepstakes started in May, 1901, in a shop at Cass Avenue and Amsterdam Street in Detroit. Working with Henry Ford were Oliver “Otto” Barthel, the overall project engineer, and Ed “Spider” Huff, who was responsible for the electrical and ignition systems, and also was Ford’s riding mechanic. They were assisted by Ed Verlinden, a lathe operator, Charlie Mitchell, a blacksmith, and George Wettrick, a lathe hand and engine assembler.

1901 Technology

The car’s frame is made of ash wood reinforced with steel plates, suspended on its front and rear axles by leaf springs. The axles are located by a Ford-patented “reach-rod” system. The wire-spoke wheels are 28 inches in diameter, fitted with four-inch-diameter tires from the Diamond Rubber Company, which eventually became part of BFGoodrich Tires. These were an early form of “tubeless” tire, in that the tire is a one-piece circular tube with bolts embedded in the rubber for attaching it to the wheel rim.

The engine is mounted in the middle of the car on the left-hand side, under the seat. It has two cylinders, horizontally opposed, with the crankshaft aligned transversely across the chassis. The cast-steel connecting rods reflect steam-power technology, with brass crank bearings as separate pieces bolted to the ends of the rods. The block and pistons are cast iron and, with a seven-inch bore and seven-inch stroke, the total displacement is 539 cubic inches.

The cooling system holds eight gallons of water, circulated by a pump located on the outboard side of the engine. The pump is driven by a chain from a gear on the outboard end of the crankshaft.

The fuel tank holds approximately five gallons of gasoline, fed to the engine by gravity.

The engine oiling system is simply a series of drip mechanisms that deliver oil to the desired locations. Since the crankshaft spins in the open, a lot of oil is thrown around when the engine is running, soon covering not only many external parts of the car, but also the driver and riding mechanic. This was called a “total-loss” oiling system, because none of the oil is recovered or recirculated.

The cast-iron flywheel, mounted on the inboard end of the crankshaft, measures 24 inches in diameter and weighs 300 pounds. A secondary wheel, which fits into a flange machined into the inside of the flywheel’s rim, acts as the high-gear clutch.

Next to the high-gear clutch is the two-speed planetary transmission, with a first-gear band and a reverse band. A sprocket, mounted at the center line of the car, carries the drive chain, which runs to another sprocket on the differential in the rear axle.

According to Oliver Barthel, the engine block and pistons were cast elsewhere, but all the machining and assembly was done at their Cass Avenue shop.

Several elements in the car were innovative and technologically advanced for the time.

The induction system, then called a “vaporizer,” is a rudimentary form of mechanical fuel injection, throttled by varying the amount of intake valve opening, and the ignition system is a forerunner of today’s distributorless coil-on-plug systems. It is called a “wasted-spark” system, because the spark fires on both the compression and the exhaust strokes. Both the vaporizer and the spark coil system were patented by Ford.

The “Huff” ignition system was innovative because it has porcelain insulators on the spark plugs. Spark plug fouling was prevalent in those early engines, so Ford and his team engaged the services of a Detroit dentist, Dr. W. E. Sandborn, to make ceramic insulators for their plugs. The electrical insulation gives a hotter, more consistent spark. In fact, after the 1901 race Alexander Winton bought several of Ford’s spark coil systems for his cars.

Fifty-one years later, Barthel said he believed they were the first porcelain-insulator spark plugs made anywhere.

In the same reminiscences, recorded in 1952 for the Henry Ford Museum Archives, Barthel described their first test session: “The first trial run was made in July, 1901, on the north boulevard over a measured half mile. It was timed by an electric timing device that Huff and I had specially made for this test. This section of the boulevard was closed off by a special police guard for the duration of the test. The timer recorded the speed for this straightaway test run at the rate of 72 miles per hour.”

While there are no records or descriptions about how Sweepstakes was operated, from the positions of the controls it is reasonable to assume that Henry Ford operated the steering, the throttle lever, the reverse gear pedal, the gearshift lever, and the brake lever. From his position crouched on the left running board, the principal job of Huff, the riding mechanic, was to counter-balance the car in the turns. He also would operate the controls for spark advance, the ignition on/off switch, and the oiling system if necessary.

First-Time Winner

Sweepstakes carried Henry Ford to victory in the first and only race he ever drove — the race against Alexander Winton on October 10, 1901, in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. Since Ford was the underdog, and the local favorite who defeated one of the best and most successful racers in the country, his victory was popular and widely publicized.

In fact, Ford’s win changed everything for him, and ultimately for the history of the auto industry. Several people watching that day came forward with offers of financial support, which set him on the road to establishing Ford Motor Company in June, 1903. Ford went on to prove his belief in low-cost production with the Model T, the car that put the world on wheels.

The Sweepstakes Saga

Following Ford’s October, 1901, victory, he received several offers from people who wanted to buy his race car. “Ford’s machine caused a lot of talk among the visiting chauffeurs,” reported the Detroit News on Oct. 11, “and one of the best of them is today dickering to buy the car or a new one made on the exact pattern.”

However, Ford did not sell Sweepstakes until March of 1902. That was the same month he left the Henry Ford Company (which ultimately became Cadillac), his second manufacturing venture, launched after the October, 1901 race. Ford was dissatisfied with his situation there, and wanted to build better, faster race cars. The 999 and Arrow were the results, appearing later in 1902.

William C. Rands bought Sweepstakes for approximately $2,000. Rands, who owned a bicycle store on Woodward Ave., entered it in several races with a driver named Harry Cunningham, who also on occasion drove the Arrow for Henry Ford and Tom Cooper.

As the auto industry grew, Rands became a large aftermarket supplier of such parts as convertible tops and windshields, and he offered Sweepstakes back to Henry Ford sometime in the early 1930s.

By then it had been stored in a warehouse for many years, and the wooden body had been destroyed in a fire. Ford had new bodywork made to restore the car, and promotional photographs taken in the ’30s show that the result of this work was not an exact replica of the original.

After this point, the car was stored at the Henry Ford Museum and, over time, all but forgotten. With no papers to verify it as the original Sweepstakes, museum personnel came to believe it was a replica built by Henry Ford in the ’30s.

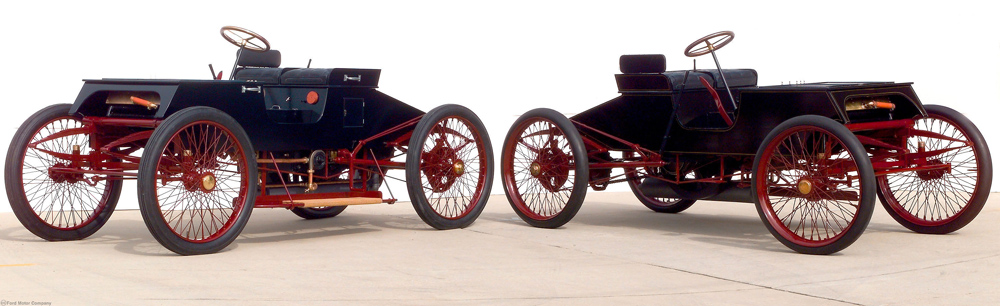

It wasn’t until the approach of the 1901 race’s100th anniversary that steps were taken to verify the car’s authenticity. Restoration of the original Sweepstakes, along with the building of two working replicas, began in preparation for the Ford Racing 100th Anniversary celebrations.

Gallery

You must be logged in to post a comment.